Mind the output gap

The unemployment rate is our best real-time gauge of how hot the economy is running.

Modern central banks have, to a greater or a lesser degree, converged on the concept of the output gap as the key predictor of inflation. The idea is that there is some level of potential output in the economy that is neither inflationary nor disinflationary. If actual output is above its potential, the inflation rate will rise; if the economy is below its potential, the inflation rate will fall or even turn negative.

Note that this idea of ‘potential’ output will be somewhere south of the economy’s actual physical capacity. It is possible to operate above potential for a while, by bidding up to secure more workers, materials and so on. But once you get into an economy-wide bidding war, you can only maintain that level of activity at the cost of ever-increasing upward pressure on prices.

On the other side of things, if the economy is running below its potential, that implies there are some resources that are going unemployed due to a shortfall in demand. In this case, you would expect prices to fall. (More accurately, to fall short of intentions – maybe you end up with 1% inflation instead of the 2% that the central bank is aiming for. But I won’t complicate the story more than is necessary.)

This framework makes monetary policy sound like a quite mechanical task – just use interest rates to dial the economy up or down relative to its potential, until you get the inflation rate you’re looking for. But there’s a glaring problem: we can’t observe what potential output is, or was, or will be.

Sure, we have some idea of what it should look like. Firstly it should evolve gradually over time, in response to things like population growth, productivity improvements and the extent of our investment in physical capital. Secondly, the relatively stable inflation of the last 30 years suggests that we’ve been running close to our potential on average, spending roughly the same amount of time above and below it. Together these suggest that we can use some sort of filtering method to extract a trendline from the actual GDP data. But beyond that, there’s no agreed method for estimating potential, and no two people will come up with the same answer. So any claims about the output gap need to be taken with a grain of salt.

Both the ANZ economics team and Michael Reddell have recently noted the IMF’s estimates of global output gaps, from its latest World Economic Outlook. Reddell makes the point that the IMF uses a consistent method across countries, so even if we have doubts about the absolute numbers, we should be able to take something from the relative rankings. According to the IMF, New Zealand is expected to be the most overheated of the advanced economies this year – running almost 2% above its non-inflationary potential. That’s despite the RBNZ having started the process of cooling down the economy earlier than most other central banks.

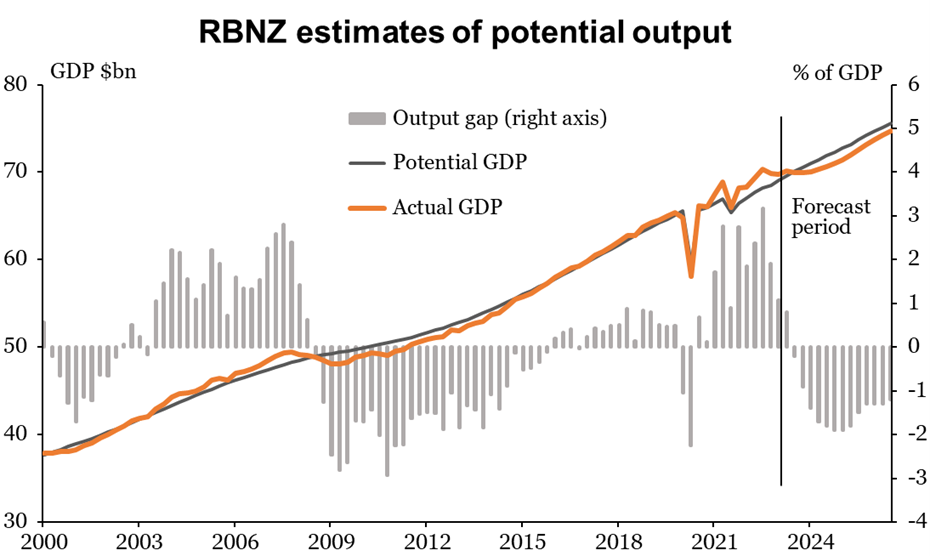

For comparison, here’s the RBNZ’s own estimates of the output gap, taken from the August Monetary Policy Statement. By their reckoning, the gap had already narrowed to around +1% of GDP by early this year, and was expected to have closed altogether by now. Getting the output gap down to zero is not enough though – not only is current inflation high, but people expect inflation to be high in the future as well. In an output gap framework, to bring inflation expectations back down in line with the 2% target, the economy needs to spend some time operating below its full capacity. Not necessarily shrinking, but not catching up with the growth in potential.

The ‘filtering’ approach to estimating potential output has some similarities with how seasonal adjustments are calculated, which I discussed here. It also has similar pitfalls. In particular there’s the end-point problem: the estimates for the most recent history can be revised substantially each time you add a new observation. That problem is exacerbated if, as is common, you include your own forecasts of GDP in the calculation – people with different views on future growth will be left with different estimates of what potential output is today. And let’s not forget that GDP itself can continue to be revised for several years after the initial release.

All together, this means that GDP-based estimates of the output gap are not merely uncertain, they’re also not stable over time. And that’s a huge problem for policymakers, because policy decisions are made in real-time, not with the benefit of hindsight.

I’m going to show two charts that I put together many years ago; the results were so stark that they changed my thinking as a Reserve Bank watcher. The first chart is a history of the RBNZ’s calculations of the output gap. The gray line is their real-time estimates: what they believed the current output gap to be at each quarterly Monetary Policy Statement. The orange line is what they now estimate the historic output gap to be, with the benefit of many years of revisions.1

Let’s be frank, the real-time estimates are a disaster – not just in terms of the size of the gap, they frequently get the sign wrong as well. Of course the decision makers at the RBNZ wouldn’t act solely on these output gap estimates, but… they would also struggle to justify acting against them.

The episode that stands out in my mind is the OCR increases in 2014. The RBNZ lifted the OCR in four steps from 2.5% to 3.5% and, at least in the early stages, was flagging that it expected to reach 4.5% or more. At the time, the RBNZ believed that the economy had returned to its potential and would soon move into ‘hot’ territory (the rate hikes were meant to be pre-emptive).

Today, the RBNZ finds that the economy was still substantially below its potential at the time – indeed the output gap had barely improved from the depths of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. From today’s vantage point, it should be no surprise that inflation did not take off – in fact it fell further below the 2% target – and that the OCR hikes were reversed a year later.

Interestingly, there seem to have been the makings of a policy mistake in 2019 as well, when the RBNZ reduced the OCR further despite inflation rising above the 2% target, an unemployment rate close to 4%, and wage growth accelerating for the first time in a decade. At the time, the RBNZ believed that the economy was starting to fall below its potential; today’s estimates show that it was actually running a bit hot. We’ll never know, but I imagine that if Covid hadn’t happened, we would have seen interest rates rising again in 2020.

The next chart here is the kicker. If you plot the RBNZ’s current estimate of the historic output gap, the one that’s benefited from years of revisions, it looks pretty much like the inverse of the unemployment rate. And unlike GDP, the unemployment rate doesn’t get revised over time (not by any meaningful amount). What that means is: the unemployment rate can tell us, in real time, what GDP can only tell us with years of hindsight.

As I said, these charts changed the way I think as a Reserve Bank watcher; they made me realise that I need to spend a lot more time understanding the shape of the labour market and how to interpret the data. The unemployment rate is great – it’s the single best indicator of how the economy is currently faring – but you should never rely on just one indicator, and you certainly shouldn’t take it at face value at all times.

The way I’ve drawn the chart above, to make the two lines overlap, means that the zero line for the output gap intersects at a 5% unemployment rate. In other words, 5% appears to be the rate that’s consistent with inflation neither rising nor falling – the infamous NAIRU concept.2

But I wouldn’t read it that literally. For one thing, that interpretation requires that the NAIRU has been constant for the last twenty-odd years. I don’t think that’s the case; there’s good reason to think that it’s been gradually coming down over that time. One important factor is demographics. Older cohorts have much lower unemployment rates, and those who can’t find work are far more likely to count themselves as ‘out of the labour force’. So as those older groups make up a bigger share of the population, they will tend to drag the average unemployment rate down.

A few years ago I crunched some numbers on the impact that this, and other demographic changes, might have had on the NAIRU. It was all very imprecise, but my best guess is that NAIRU today is in the range of 4 to 4.5%. That’s down from around 5% in 2007, the last time that the labour market was this stretched.

That brings us to yesterday’s labour market surveys. An unemployment rate of 3.9% is getting closer to what I would consider to be the range of NAIRU, and I expect we’ll be within that range at the end of the year. So my impression of the output gap is much closer to the RBNZ’s than the IMF’s.

My ‘revelation’ about the unemployment rate is also why I’m mildly in favour of retaining the employment objective in the RBNZ’s Remit. Not as a numeric target of course, and it’s never been seriously proposed as one. I’d argue that it’s not even a “dual mandate” as it’s often described. To me the wording implies that the employment objective is secondary: the RBNZ is required to achieve and maintain price stability, but only to support maximum sustainable employment. (With the central government presumably taking the lead role in the latter.)

The value of keeping the employment objective in there is that it compels the RBNZ to think harder about what it can learn from the labour market. In an ideal world it wouldn’t be necessary – the RBNZ would already seek out any and all information that could give them an edge. But their past record suggests that, for whatever reason, some insights were going astray.

For anyone looking to replicate this: unlike the previous chart, these are annual averages. In the earlier years the RBNZ only published annual estimates (for the year to March); I interpolated these to get current-quarter estimates. At some point the RBNZ started to publish quarterly figures, but I’ve used the four-quarter average to keep them consistent with the earlier data. I cut the chart off after 2019 because the Covid lockdowns fouled up any notion of what ‘potential output’ might be; the RBNZ did continue to publish estimates in that time, but I’m certain they weren’t calculated in the same way as previously.

The idea of a ‘neutral’ or ‘natural’ unemployment rate is a controversial one, and some argue that such a thing doesn’t exist at all. Like potential output, it’s another ‘unobservable’ that no two people will agree on, but I think the bounds of uncertainty are narrow enough for it to be a useful concept. The role of NAIRU in monetary policy is also frequently misrepresented by critics on the left. For an example of this - as well as some great archival footage - I highly recommend the 2002 documentary “In a Land of Plenty”, which you can watch here.)