Make Inflation Transitory Again

The US has had remarkable success in achieving a soft landing. But Americans don’t seem much interested in asking why their experience has been so different.

For anyone trying to understand what’s going on with the economy, it can be frustrating to see economists with wildly different views about the future. It gets worse though: sometimes we can’t agree on the past either.

The last four years have been incredibly dramatic for the world economy. Huge swathes of activity shut down and then reopened; billions of dollars created by central banks for governments to spend; unemployment surging and then falling to record lows; and the return of inflation as both an economic and a social issue.

It’s possible to explain all of this by boiling it down into Economics 101 terms: we had a series of demand-side and supply-side shocks, which have been evolving over time. But I’m wary of taking that too far. You can always tell a just-so story of supply and demand that fits the data perfectly, but that doesn’t necessarily make it an accurate description of what happened.

What we see instead is that many economists emphasise one side over the other - particularly those advocating for a certain policy response. We’ve seen this most prominently in the debate about the causes of and cures for inflation in recent years.

The first hints of a resurgence in inflation came in early 2021. While reported inflation was still low in the wake of the Covid shock, a growing number of businesses were grumbling that their costs were escalating, and that they’d soon have to pass it on to their customers. A few people muttered darkly about the perils of low interest rates and money printing. But many prominent economists argued that this was just a one-off adjustment, a view that came to be dubbed ‘Team Transitory’. The argument went something like this:

“Costs have risen because global supply chains have become gummed up - capacity in the shipping industry has been idled, and with ports and factories operating under health restrictions, everything is taking longer and costs more. But these aren’t a source of repeating price increases. And once those initial price rises have worked their way through, we’ll still be left with an economy that’s taken a massive blow from Covid; demand is going to stay weak for a long time. You don’t want to make it worse by piling on with higher interest rates.”

The first part of that was true enough. But as time passed, it became apparent that this wasn’t the only thing going on. Economic activity didn’t just return to its pre-lockdown level, but rose well above it. Similarly, unemployment rates more than reversed their initial rise, and fell to record lows in some cases. And prices started to rise rapidly in areas that were well beyond anything you could pin on global trade.

All of these were signs of too much demand. Governments and central banks had expected Covid to look like a ‘normal’ recession - and to be fair, in the heat of the moment in March 2020, there was little reason to think otherwise. So they acted to fill the expected shortfall in demand, through fiscal stimulus programmes and low interest rates. But as the lockdowns were lifted, it became apparent that the nature of this recession was different - demand hadn’t fallen, it had just been suppressed. Adding unprecedented amounts of stimulus on top of this just sent the economy into overdrive.

There’s usually a lag between an economic boom and a rise in inflation, and it took longer to show through in some countries than in others (New Zealand was among the earlier ones). But by mid-2022 most central banks had conceded the point, and were lifting interest rates rapidly. Team Transitory fell out of favour.

The standard view of monetary policy is that once inflation takes hold, you need a period of weak activity to squeeze it out of the system again. To use a more technical term, you need to flip the output gap from positive to negative for a period of time. And that’s more or less where we are today: interest rates rose, the economy slowed, and we’re just waiting to confirm whether inflation is on track to return to the 2% or so that central banks are aiming for.

But something curious has been happening in the US over the last year or so. Interest rates are still high, but the economy has if anything been accelerating again. And yet they’ve probably had more success than any other country in bringing inflation down. This is the fabled ‘soft landing’ that is often talked about but almost never achieved, and it’s not at all clear how much of this is down to good economic management versus luck.

And amongst these results, Team Transitory has returned from the wilderness. Their argument now goes:

“See, I told you that if you waited long enough, those cost pressures would take care of themselves. Sure, annual inflation is still high, but if you look at this measure of ‘core’ inflation that I invented, it’s been running at the equivalent of 2% for the last six months, so it’s only a matter of time before that’s reflected in the 12-month rate. We didn’t need a recession to get this result, and we certainly don’t need interest rates to stay as high as they are today.”

You can probably tell that I’m sceptical of this view. But the ‘team’ includes some economists that I really respect, so I should have a serious answer as to why I disagree with them.

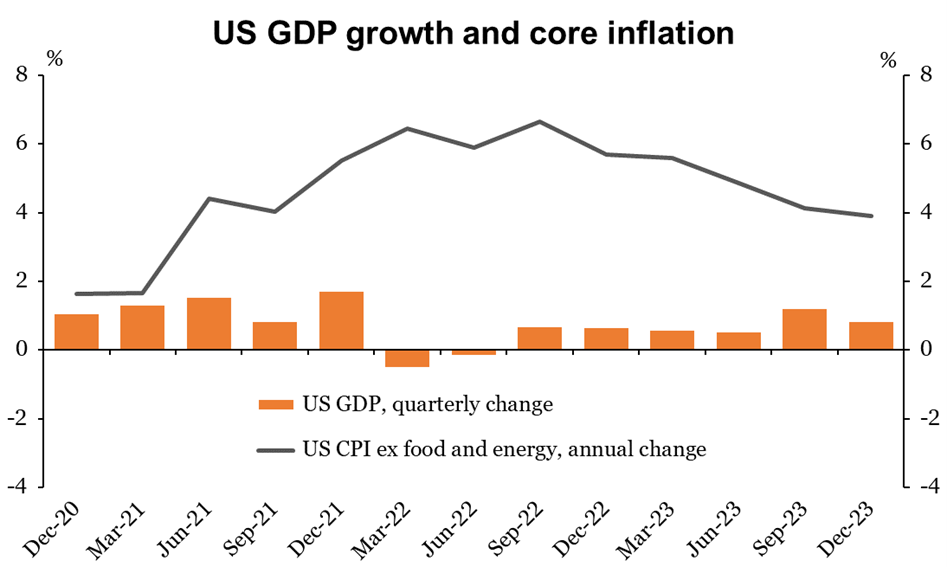

The Twitter version of the argument is summed up in the chart below. The orange bars are quarterly changes in GDP; the grey line is the annual rate of core inflation, which in this case means excluding food and fuel. (The question of what we actually mean by ‘core’ inflation is worth a post of its own one day.)

Just from eyeballing the chart, it seems like something was keeping both inflation high and growth weak in early 2022. Then that ‘something’ went away, and inflation fell and growth rebounded. These are the textbook symptoms of a temporary supply-side shock. Case closed!

Not so fast. For one thing, the timing doesn’t line up. Inflation may have peaked when growth was weak, but it was ramping up at a time when growth was very strong. And it’s a stretch to say that the supply chain issues were at their peak as late as 2022.

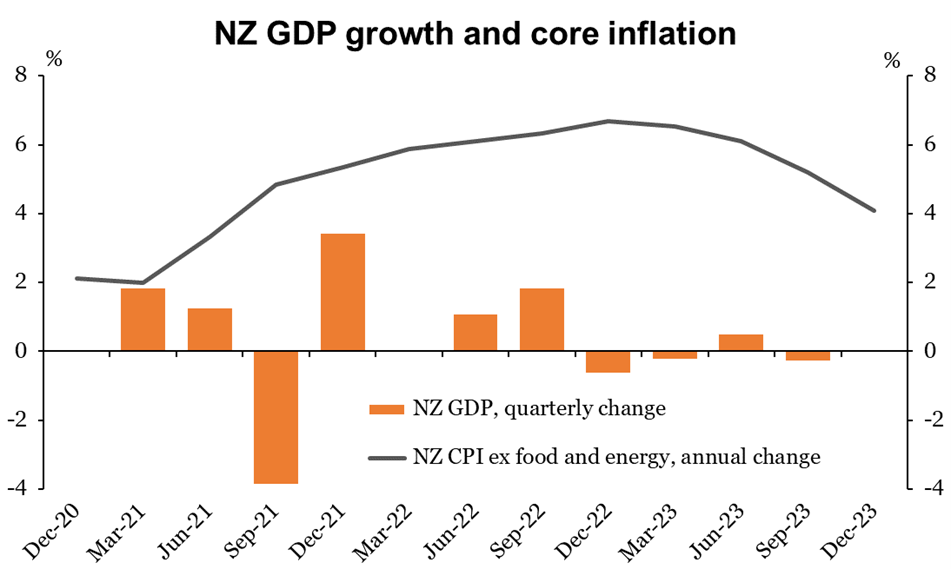

The bigger issue I have with this chart, though, is what happens when you draw it for other countries. Here’s what it looks like for New Zealand:

It’s not just that inflation peaked later here; it took a period of weak or even negative growth to start bringing it down again. (GDP for the December 2023 quarter hasn’t been published yet, but from the indications so far, there’s a good chance it could be another negative.)

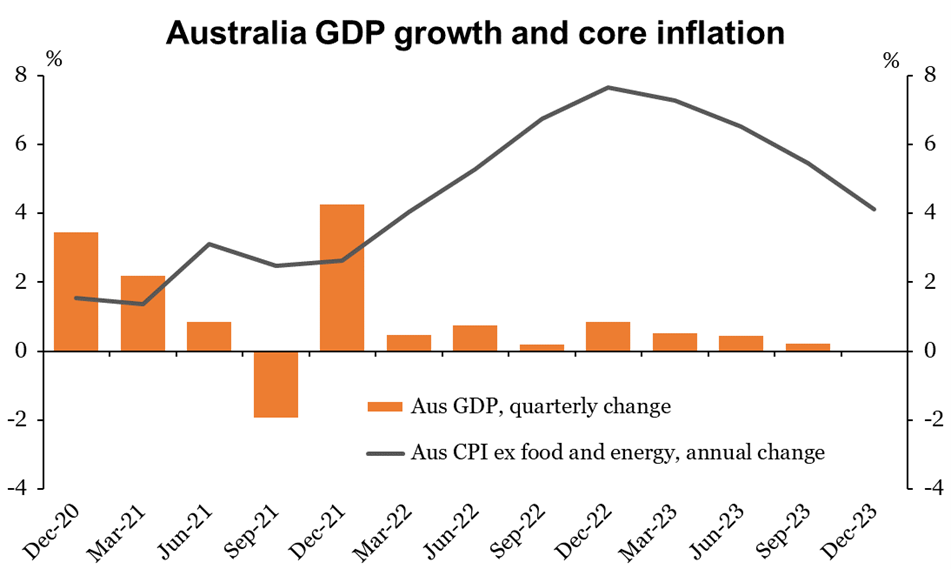

Here’s the same chart for Australia, a country that on the whole has had a better run of things over the last year. But again, it look a long period of slow growth before inflation started to come down.

Do the same again for Canada, or the UK, or the euro area… without swamping you with more charts, it soon becomes clear that it’s the US that has been the outlier.

Unfortunately, you won’t often hear it described in those terms. The US is at the heart of the global economy, and most of the economic commentary and analysis that we hear comes from there. From their point of view, the US is the norm, and anyone that’s different is an exception. And if the US experience doesn’t match the theory, then it’s time to ditch the theory.

I don’t have a straight answer as to why the US has fared so differently. I suspect it goes beyond the simple stories of supply and demand, and into the complexities of how the US economy is structured. For instance, their more employer-friendly labour laws may have stopped a wage-price spiral from gaining traction. Or perhaps it’s because a stronger US dollar has helped to suppress imported inflation. (By construction, a rising US dollar means that some other countries’ currencies must be falling.)

No doubt there are other factors, and you probably won’t find two economists who agree on their relative importance. But it would be nice if those who are most familiar with the US economy could turn their minds to why its success might be difficult for other countries to replicate.