Why are Jobseeker benefits still so high?

Probably a combination of definitions and forbearance. In any case, it's not reason to question the official unemployment figures.

Posting here is going to be a bit light for the next few weeks, as I have some family time planned. Indeed, I was struggling to get something ready for this week before I go away, until this fell in my lap: Stuff had a story yesterday asking why the number of people receiving the Jobseeker Support benefit has never fallen back to its pre-Covid levels, when every other indicator has pointed to record low unemployment and severe labour shortages.

To recount the facts: there were around 145,000 people receiving the Jobseeker benefit at the end of 2019. At that time, the official measure of unemployment from the Household Labour Force Survey (HLFS) was around 116,000 people, or 4.1% of the labour force. Both measures shot up after the Covid shock in 2020 (notwithstanding some definitional issues in the HLFS at first - a lot of people were counted as ‘not actively seeking work’ because it wasn’t feasible to do so in a lockdown). However, while HLFS unemployment soon fell below pre-Covid levels as the economy became overstimulated, benefit numbers were slower to recede, and even now they remain much higher than before.

The Stuff article quotes a few economists on what might be going on behind these numbers. What it doesn’t mention is that the good folks at Stats NZ have already done a lot of digging on this. They published this paper last year, using confidential data to try to match HLFS respondents with benefit recipients, in order to identify the overlap between them. This was also presented at the NZAE conference last year - I heard that the room was packed for this session, so there are plenty of economists who could tell you about it.

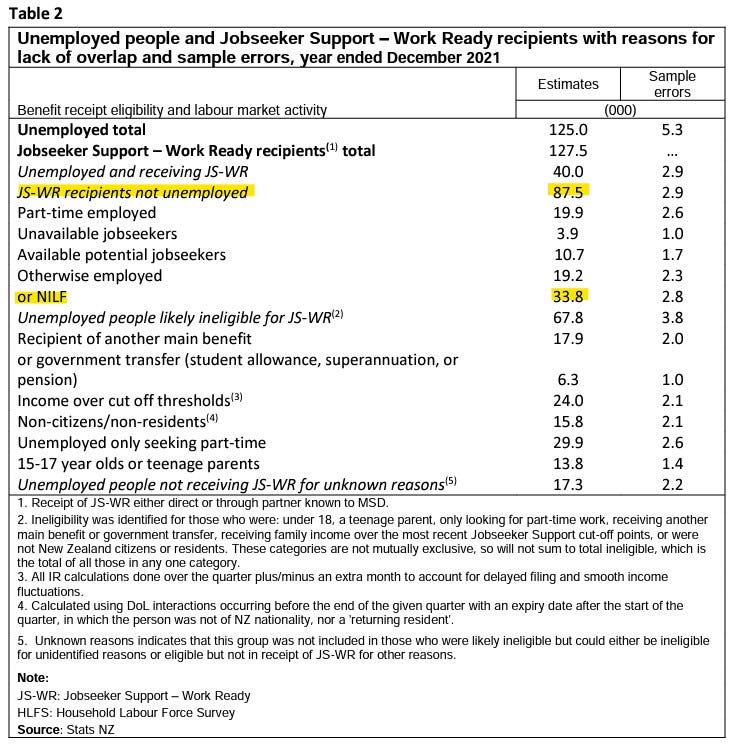

As the diagram below shows, there are many reasons why someone might fall into one group but not the other. Some of them are well-known - for instance, you can’t receive the benefit if your partner earns above the income threshold. Some of them are probably less well recognised, such as 15-17 year olds (who aren’t eligible for the Jobseeker benefit, but are counted as working-age in the HLFS), or recent migrants (you need to have lived in New Zealand continuously for at least two years to qualify for the benefit).

But one of the biggest differences is somewhat obscured by the name. The Jobseeker benefit is not ‘the dole’ as many of us are used to thinking of it. In the 2013 welfare reforms the old unemployment benefit was partly folded into the Jobseeker benefit, but it’s not the same thing. The Jobseeker benefit is aimed at assisting people into full-time work. So if you’re already working part-time, and you’re looking for something full-time, you can receive the benefit. If you’re unemployed but only looking for part-time work, you don’t qualify for the benefit.

(I should note here that the Stats NZ paper focuses on those receiving the ‘Jobseeker - Work Ready’ benefit, and that’s what I’m going to refer to for the rest of this post. There are currently around 100,000 work-ready recipients; there are another 73,000 people receiving the ‘Jobseeker - Health Condition or Disability’ benefit, and without going into that too much, I don’t think that those numbers require the same degree of explanation.)

After some careful work matching up the individual records from the two data sources, Stats NZ concluded that the overlap is about one-third, in both directions. That is, about a third of those officially unemployed are receiving the Jobseeker benefit, and about a third of those on the benefit are officially unemployed. So there’s plenty of leeway for the two numbers to differ in terms of the level. And it’s even possible that they could have different trends over the long term, depending on changes in demographics or the labour market.

However, that’s not a plausible answer for more rapid divergences, such as we’ve seen since Covid. And here’s where the forensics in the Stats NZ paper becomes really valuable.

The first clue is to go back to the chart at the top of this post. It looks like the two series were already diverging in the years before Covid - benefit numbers started to rise even as HLFS unemployment held steady (and fell as a percentage of the labour force). The chart below from the Stats NZ paper expands on this, although I find it easier to understand if I flip it around: in recent years, a growing share of Jobseeker recipients have not been unemployed as defined in the HLFS.

What’s more, the turning point looks to have been at the end of 2017 - that is, right after a change of government.

Here’s where it’s useful to get into some definitions. In the HLFS, to be counted as unemployed you have to be actively looking and available for work. ‘Actively’ is the crucial word; it needs to be more than just browsing through TradeMe Jobs. If you don’t meet that standard, you’re counted as not in the labour force (NILF). Some people consider this definition to be too narrow, and advocate for broader measures of labour market slack such as underutilisation. But the advantage is that it’s been defined consistently over the history of the survey. So whatever you think of the level, you can be reasonably confident that changes over time are genuine.

The Jobseeker benefit also has work-search requirements, but these haven’t been consistent over time in the way that the HLFS has. Even if the rules themselves aren’t changed (and they weren’t in this case), how strictly they’re enforced is at the discretion of the government of the day.

This is not to say that there’s something wrong with the current approach. Some might argue that the previous government enforced the rules too strictly, pushing people into low-quality jobs; that’s a matter of judgement. And those who have had to go through the system would probably never tell you that it’s felt ‘lenient’.

OK, so there was already an emerging upward trend in benefits before Covid; in that sense, you could argue that benefit numbers actually are back to their pre-Covid trend. But that still leaves a sizeable gap to explain over the last few years - remember that HLFS unemployment is not just back to pre-Covid levels, but has been substantially below it.

The last piece of evidence that I wanted to note from the Stats NZ paper is the table below, which breaks down the reasons that people might fall into only one category or the other. This is a snapshot of the December 2021 quarter, which is well past the initial employment shock (though it’s still not the ideal point of comparison, as some of it was spent in the second Level 4 lockdown).

What I’ve highlighted is the group who were receiving the Jobseeker benefit, who were ready to work, but were not officially counted as unemployed - over 87,000 people in that quarter. The single biggest subgroup here - nearly 40% - were actually counted at not being in the labour force at all. In other words, whatever they were telling MSD, they didn’t meet the (probably stricter) HLFS criteria for actively seeking work.

So the Stats NZ paper gets us about 90% of the way to an answer. What we’d really like to have is a version of the ‘Table 2’ above for the December 2019 quarter, to give us a before and after for the Covid shock. My guess is that the big increase in Jobseeker recipients was in the NILF group, but it’s just a guess. (I could ask Stats NZ to crunch those numbers, but I suspect that it’s a lot more work than they’re willing to do for free.)

To wrap it up, I don’t think there’s a lot here for us to worry about. When you’re getting mixed messages, go with the official series, because among other things we know that it’s been measured consistently over time. And while it may not be obvious from eyeballing the first chart, the gap between the two series has been steadily narrowing again since late 2021.

And despite what I suspect is a firmly-held view in some circles, benefits aren’t a big part of the government’s books. In the latest year, Jobseeker and emergency benefits cost about $3.5bn, compared to total spending of almost $162bn (and an operating deficit of $10bn). Cracking the whip on jobseekers just isn’t going to make much of a dent in that.

Maybe the reason that the Stats NZ paper/conference wasn't mention is because most of the economists that are typically interviewed in the media don't come to the annual conference (usually bank economists or consultant of some sort)?