Do we need a monthly CPI?

It wouldn’t hurt, and it’s not hard to do, but the upside isn’t huge either.

One of the sly secrets of economic forecasting is how theory-free it can be – often it’s just a matter of understanding the recent past and extrapolating from it. The more we know about that recent history – the faster and the more frequently that data is made available – the less extrapolation is required. So if you ask an economist if they’d like more data, especially if it’s at no extra cost to them, then the answer will always be “yes”.

To be fair, there are some cases in New Zealand where timelier data seems like a reasonable ask, given what other countries are capable of. GDP – a measure of output across every sector of the economy – is a big task that most OECD countries only attempt once a quarter, but New Zealand is one of the slowest to publish the results (two and a half months after the end of the period). We’re the only one that doesn’t have a monthly labour market survey, although the monthly employment indicator which is drawn from tax data is a welcome addition. And until recently, the only countries not reporting consumer prices on a monthly basis were New Zealand and Australia.

However, since last September the Australian Bureau of Statistics has been publishing a monthly CPI indicator, with a history backdated to late 2017. Here’s how it has performed:

It’s been a bit choppy so far – bursts of inflation, followed by pauses. That’s the inevitable trade-off with higher-frequency data: there’s a lot more variability that would otherwise be hidden within a quarter. With a monthly series, there are times that you’ll spot a new trend sooner, and other times that you’ll be led astray by noise.

It’s important to note that the Australian indicator is not a ‘true’ monthly CPI in the same way that we see in places like the US. Within the quarterly CPI, the frequency of the data collection varies by item. Some things like food and fuel are surveyed monthly or even weekly, and then averaged over the quarter. Generally this happens where prices are clearly posted and the nature of the product doesn’t change over time (or it’s obvious when it has changed – stats agencies are wise to shrinkflation in packaged food.)

Where the data collection is more labour-intensive, it’s done once every three months, either by recording prices on store shelves or by sending a survey to businesses. This tends to happen where the stats agency needs information about the product’s features in order to make quality adjustments (an issue especially for electronic goods), or where businesses provide a quote rather than an advertised price (which is the case for many services).

The Australian indicator simply takes the existing data set for the quarterly CPI and releases it in stages. In any given month, only about two-thirds of prices are updated – those that are measured monthly, and the quarterly items that were surveyed that month. (In New Zealand, these are generally done in the middle month of the quarter.)

Could we do the same thing here? Yes. In fact, the three-yearly CPI Advisory Committee canvassed this option way back in 2013. The response at the time was fairly lukewarm – my comment was that if there wasn’t any additional data being collected, a staggered monthly release would just add noise without providing much signal. That said, there wasn’t much interesting going on with inflation at the time; I imagine that it would get a much more positive reception today.

However, the plot thickens here when it comes to our Australian friends. This year’s Federal Budget provided funding for a range of modernisation measures at the ABS, including a genuine monthly CPI. I don’t know what the timeline is on this, but once it happens, it will leave New Zealand as a clear outlier in not having a monthly CPI.

One counter to this is that, unlike in Australia, a fair amount of the CPI is already available here on a monthly basis. Stats NZ has long been publishing monthly food prices, which make up close to 20% of the CPI. In recent years they’ve also been producing a monthly rental series, which is another 10%. Fuel prices are monitored weekly by MBIE, giving us another 5% or so. And there’s a handful of items like council rates and education fees which only change once a year, so for 11 out of 12 months you can confidently plug them in as a zero. All up, we already have around 40% of the CPI on a monthly basis, including some of the most variable items.

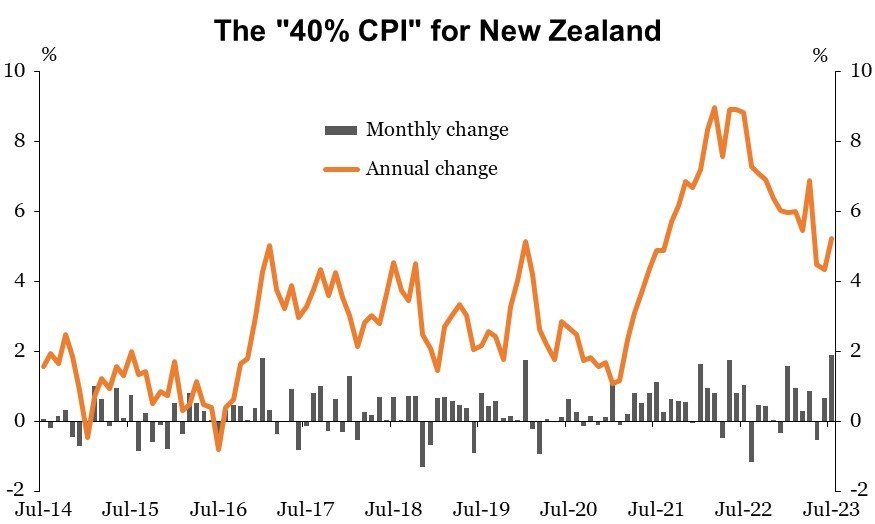

Is that 40% enough to be useful? Here’s what it looks like if we create an index from it:

The recent jumpiness in the annual rate is due to the temporary reduction in fuel excise after the Ukraine invasion. That came into effect in April 2022; fuel prices kept rising for a few more months before easing off; then the annual rate spiked again in April 2023 as the excise cut dropped out of the calculation. The pickup in July is entirely due to the end of the excise reduction; without that, the annual rate on this measure would have dropped to 3.5%.

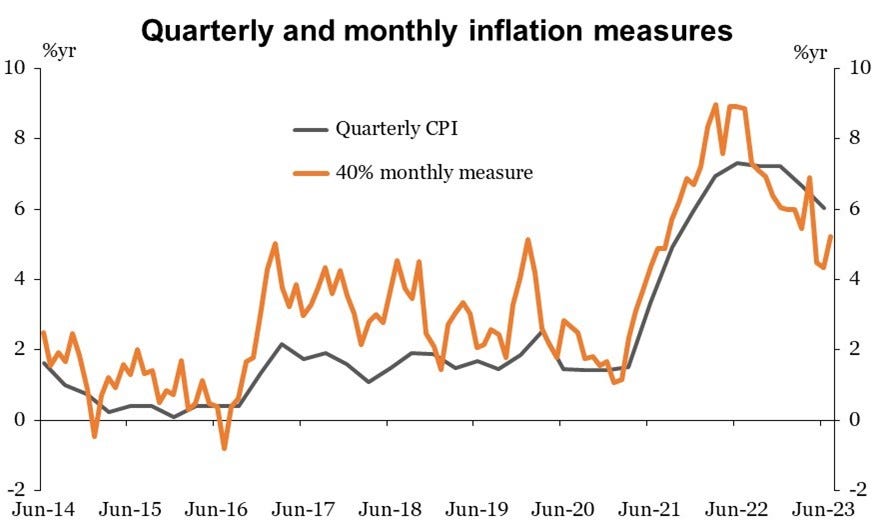

Here's how the partial monthly measure looks against the full quarterly CPI:

It’s not a bad effort, in terms of capturing the broad swings in inflation a little sooner. But there are times when there are some clear gaps. One is household goods, largely imported, which were a persistent source of low inflation through the 2010s. The other one is services, which in the last year have taken over from goods as the biggest source of inflation.

Some countries, particularly the US, have seen their annual inflation rates slow sharply this year, raising the question of why we haven’t seen the same progress here. What the monthly measure shows is that we have – at least in the areas that were always rightly regarded as ‘transitory’. The issue in New Zealand is that inflation seems to have spread into wages, and from there into prices for labour-intensive services, more so than for some of our peers.

Where this leaves me is: yes, we probably would benefit from more frequent updates on the other 60% of the CPI. As I noted earlier, this is largely stuff that takes more effort to measure. That’s hardly an insurmountable problem though, since other countries do it; it’s just a matter of resourcing.

The 2013 CPI Advisory Committee costed a full monthly CPI at around $3.3m per year; let’s call it $5m in today’s dollars. That would be a fair chunk of Stats NZ’s budget (about $200m a year outside of Census years) for just one series, so you can understand why they haven’t done it off their own bat. But in the context of total government spending of over $150bn a year, it’s a drop in the bucket.

So there doesn’t seem to be a strong argument for not doing it. But what are the benefits? Fewer headlines about stale data, for one thing. Economists look smarter because there are fewer ‘surprises’ saved up for them every three months. But they’re not the primary audience for this. As the CPI Advisory Committee notes:

“The principal use of the CPI is to inform monetary policy setting.”

Keep in mind that the CPI is not a measure of the cost of living. It’s close enough that we often use that as a shorthand, but there are some big items, like interest payments, that are specifically left out because they would muddy the waters for monetary policy purposes.

With that in mind, the purpose of a monthly CPI would be to reduce the chances of a monetary policy mistake. But how do we define a mistake? We long ago moved away from a ‘hard’ inflation target, where the RBNZ is expected to keep inflation within a range at all times. These days, central banks are generally tasked with managing inflation over the course of the cycle.

In that respect, it’s very difficult to brand any single OCR decision – which is where a monthly CPI might make a difference – as a ‘mistake’. And even if it were, there’s usually another opportunity in six weeks’ time to correct it.

Ultimately, the issue is that what we really want to know is something that no statistician can tell us: the future. Information about the recent past can help, but mostly for the near term – not the horizon over which monetary policy can make a difference. At some point we have to resort to our models of how we think the economy evolves – and accept that this is where the really consequential errors will come from.

I do think we’ll get a monthly CPI before too long – the RBNZ wants it, and they’re the ones who should have the most say in it. But we should temper our hopes for how much difference it would make to our economic performance.

Interesting read Michael. What's your take on monthly GDP data as well? Does the NZAC effectively do the job and so should be more formalised?